The Pennine Way

2009-04-11

In the spring of 2009, I walked the 429km1 of the Pennine Way, a national trail along the hills of northern England, in 15 days.

Setting off from Derbyshire, I hiked over the Peak District moors into East Lancashire; through the Yorkshire Dales into County Durham and Westmorland; along Hadrian’s Wall and through the Kielder Forest in Northumberland; finally traversing the Cheviot Hills to cross the border into Scotland two weeks later.

I camped along the way; carrying my tent, sleeping bag and stove on my back. Happily I was joined by my dad for two days, and my friend Jim for another two. The rest of the time, I was on my own.

Day 1: Edale to Crowden

So this was it then. I woke up on the sofa-bed at my old house in Manchester, with a bellyful of nervousness and a slight funk in the head from a cheap bottle of Bordeaux I’d swigged on Friday evening. ‘Have I prepared enough for this?’, ‘Will my dodgy knee give up after a couple of hours?’ and ‘Will everyone think I’m a twit when I have to admit I couldn’t do it?’ were all doubts stirring while I fished a teabag from my morning brew.

‘You’re walking to Scotland? No bus fare?’

Edale, the starting point of the Pennine Way, is handily located on the Hope Valley railway line between Manchester and Sheffield, and I’d been quite looking forward to that little journey to begin my walk. The train was delayed by some violent-looking types who—from what I could hear over the reassuring Guided By Voices in my headphones—were flatly refusing to buy any tickets. I think the inspector gave up in the end. Gorton, Romiley and Chinley all flew by, I hauled my rucksack off and up to the Old Nag’s Head Inn and put the compass lanyard around my neck.

‘Did they set alarm clocks for early morning trouble-causing? That’s dedication to the art.’

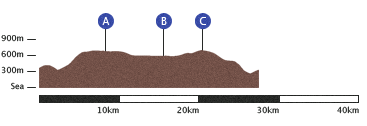

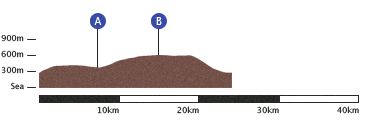

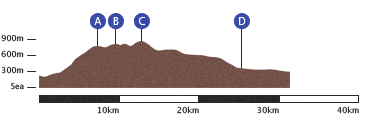

A couple of other parties were getting themselves together as I set off, and I quickly passed a group of sweet-looking girls on the first path and, feeling brave by now, gave them each a smile and ‘Good morning!’. Soon I was climbing Jacob’s Ladder up to Kinder Scout (A), and the soft, green hills and day-walkers of the southern Peak District were promptly replaced by the fiercer, lonely Dark Peak.

The guide2 recounts this section as a ‘lunar terrain of gritty pebbles and bare black peat.’ The rusty patches of moss made me think ‘martian’ a better descriptive. Not that I’ve been to Mars recently. Once past Kinder Downfall I was into my first proper wilderness stretching out to to Snake Pass (B).

As I paused by the side of the road for sandwiches and a swig from my hipflask, a chap coming the other way stopped briefly for a chat. He’d been up checking out one of the WWII aircraft wrecks lost up there in the mist.

The route up through Devil’s Dike to Bleaklow (C) was as cheerful as these sobriquets suggested3: walls of peat leaned over me, hailstones pinged off my cheeks and the path became an indistinct stream bed which forked unnervingly. I didn’t hang around at the windy summit and followed the steep edge round and eventually down to Torside Reservoir. All that was left was to pass through the calm wood on the other side and watch some sheep headbutting each other before finishing the day at Crowden.

- 6.50 — Single train fare from Manchester Piccadilly to Edale.

Day 2: Crowden to Blackstone Edge

Every tendon and tissue in my lower half ached when I woke on Sunday morning, but up I got to continue the long march north. As this second leg was due to end close to Rochdale and my family home, and it being a weekend, my dad had kindly decided to join me for the day and I was looking forward to his company.

‘The map says this should be a bridlepath. Is this a bridlepath?’

‘Would you bring a horse up here?’ ‘I don’t think so. I hate horses.’

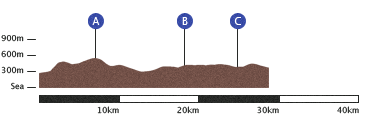

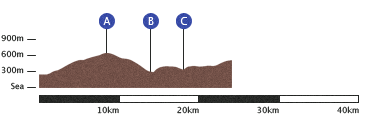

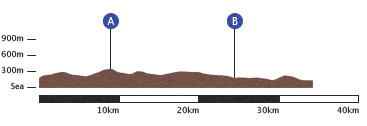

The morning was frosty, sunny and clear, which is pretty much perfect for long-distance trekking, though we had to watch for slippery ice patches. We began with a steepish climb up to Laddow Rocks, which offered a good view back over Bleaklow and the previous afternoon. From there we continued along to Black Hill (A). The column at the top is named ‘Solider’s Lump’, after the Royal Engineers who surveyed this vast boggy expanse in the 19th century—I can imagine it was a miserable undertaking. Before the path to it was paved, says the guide, ‘more than one reckless adventurer had to be rescued after getting stuck fast’ trying to reach it. Heavy stone slabs made it a bit easier for us, so we stopped for some tea from dad’s flask and a couple of biscuits.

The descent down to the Wessenden reservoirs on the other side afforded views over Holmfirth, Marsden and Huddersfield. Grouse Butts was an abrupt jump up to a long stomp over Black Moss and Rocher Moss, by which time we were both feeling a bit of fatigue. After six hours, we stopped at Standedge (B) to lunch on sandwiches and finish off the tea, using the large boulders as a windbreak. The view is south-west over Oldham to Manchester. Having first seen the city (now easier to spot at distance thanks to the Beetham Tower) from the south at the summit of Kinder Scout, viewing it from the north gave me some impression of how far I’d already walked. My pained feet confirmed.

The trudge along the edge and to White Hill felt very long indeed, but eventually we made our way down to the footbridge over the M62 motorway (C). Knowing this high crossing from the many times I’ve driven underneath it, I had been oddly excited about walking over it. It’s very noisy.

Blackstone Edge, above Hollingworth Lake, was our final ascent of the day. My mum and dad had taken us up here one sunny afternoon, maybe thirteen years before. Curiously, when we got up among the huge dark boulders I could remember the Liverpool away shirt I’d worn that day, and that my cousin Sam had been with us hopping over the rocks. We scrambled down to the White House pub where mum collected us in her car. Being so near home, I got to go back for platefuls of lasagne and a gloriously hot bath.

- 2 — Sore ankles.

Day 3: Blackstone Edge to Ponden

After a comfortable evening at mum and dad’s house on Sunday evening, I said ‘bye’ and set off again early on Monday. The first two days could’ve just been a nice weekend’s hiking not too far from home; for the next fortnight I’d be on my own.

‘Now I’ve worked out how to limp on both feet, I’ve just got to keep this up for the next eight hours.’

The start contrasted harshly with the morning before: drizzle replaced sunshine, solitude replaced chatting with dad and my heels and shoulders hurt already. I naïvely set off with my sleeping bag strapped to the rucksack, rather than inside it, and when it fell off for the second time I realised that it was already soaked.

Light Hazzles and Warland Reservoirs felt sinister as I walked along their edges, with the fog obscuring my view any further than the black water’s edge. Wet high voltage power lines crackled loudly. Following along the drain I saw a figure appear out of the cloud right in front of me: a young chap who, under his dark hood, seemed to be as glad to see another person as I was. ‘The whole thing?’ he asked? ‘I’m doing it in sections now. I’ve tried it all the way twice but didn’t make it. Once everything gets wet, it’s over.’ I glumly considered the sopping sleeping bag and tent on my back, and wondered how waterproof the backpack itself was.

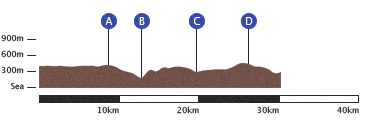

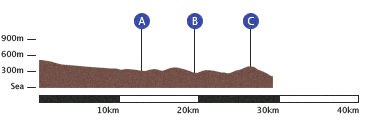

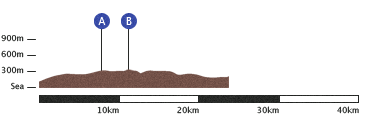

I continued towards Mankinholes and up to Stoodley Pike (A) along a path I’d taken on a circular walk with my dad a few weeks before. I was calmed a bit by the familiarity. The Pike is a monument to peace built after the defeat of Napoleon in 1814. Usually visible for miles around, I almost walked into the 38m-tall black obelisk in the blanket fog. I struggled to make out its top, staring up in the wind, and again felt very uncomfortable. There’s a spiral staircase inside which allows one to climb up in the blackness, but the idea did not appeal so I quickly set off down towards Callis Wood. Obviously, I didn’t have time to stop by lovely Hebden Bridge (enclave of tolerance and creativity among northern mill towns) and began the precipitous climb up from the valley floor at Callis Bridge (B). Heptonstall Church—where Sylvia Plath was buried—came into view soon after along the next valley.

After a long, dispiriting moor slog I dropped to a meeting of two streams at Graining Water (C) and sat in the small space of grass, sheltered from wind, to eat some lunch. Concerned about progress, I didn’t stop long before heaving my bag up past another large reservoir and then beginning another slow moor climb up to Withens Height and another literary landmark on the other side.

The ruined farmhouse of Top Withens (D) was the inspiration for Wuthering Heights in Emily Brontë’s cracker. It’s certainly isolated enough. My feet were as sore as Heathcliff, so I could think only of finishing for the day. I finally found Ponden House and paid to pitch my tent down by a stream on the old grounds of Ponden Hall, where the young Brontës would come to play and read in the library. This was literature day, then. I peeled off my socks, full of blood, and tried to clean up my blisters. I think I was a little delirious with exhaustion, as I remember forcing myself to eat some cold cheese and bread before I crawled into my damp sleeping bag at about seven o’clock. I put the Radio 4 In Our Time podcast on my headphones, and drifted through three or four episodes without listening before I fell into fitful sleep.

- 2 — Dead poets.

Day 4: Ponden to Gargrave

As you may have noticed, I had been a bit miserable on Monday. I was hoping that a new morning might bring a better mood. It didn’t. Some pissy rain made putting the tent down a pain and then I remembered I had no chance of hot food or even a tea. Gah. I’d set off from Blackstone Edge with the wrong gas canister for my stove, and foolishly thought it might be easy to pick one up along the way. I was currently two miles from the nearest anything and that was in the wrong direction. I ate my last banana and read the guide’s prediction for the morning: ‘a grey day’ of ‘moors and mires’. Best get going then.

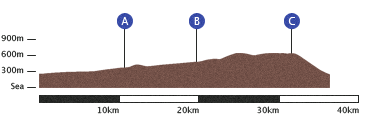

Ponden being nothing but a few farm houses, I was quickly out onto bare hills again, and striding out toward Wolf Stones (A). Thankfully the wildlife is a bit tamer now than it was back in the 16th Century.4

When I dropped down into Cowling, I became concerned because I had already drunk one of my flasks of water, was still feeling very thirsty and had most of the leg ahead of me.

To make things worse, I dropped my one full flask as I tried to unscrew it. Idiot! I checked each driveway on the way out of the village for an outdoor tap, without success.5

Gaining altitude over another couple of hills, I gave it up again easily into Lothersdale (B). There the guide and Ordnance Survey both promised a Post Office, which I thought might sell me a bottle of Volvic or a Lucozade; on arrival I was informed that it’d been closed. The day had begun to brighten just as noon passed, and I was glad of assistance from a man out trimming his hedge. He filled my water bottles up for me and I gulped away my thirst.

I got a bit lost in some farmer’s fields on the approach to Thornton-in-Craven (C), which is always irritating. I only ever notice when I get to the edge of a field and realise there’s no stile so I must shuffle all the sodding way back. However, I was still making reasonable time so I stopped by the side of a lane to eat some biscuits and nuts—all I had left to eat by then. I switched my phone on to check for messages and Livy happened to be on her lunch break so she called me. It was lovely to hear her voice, and this brief chat turned out to be my watershed in mood—everything picked up from here on and I soon reached the towpath of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Easy to follow and flat (obviously), I could admire barges and take in the afternoon sunshine.

Gargrave felt like the promised land on arrival. Not only did I spy two pubs—it had a Co-op! After finding a campsite, I set off in search of hot vegetarian food. The Mason’s Arms obliged with a cannelloni. It probably wasn’t that great but, being my first warm meal in two days, it tasted wonderful. I washed it down with pints of water and bitter, charged my phone and listened to stories from the bar stools.

‘…and she went off with that bloke, what’s his name? He came back from laying pipelines in Arabia.’

‘Oh, you mean Pipeline Pete?’

‘No not Pipeline Pete, the other one…’

I stopped by the Co-op on the way back to stock up on plasters, bread and fruit, and also found a pack of doughnuts reduced to 35p. I ate the lot for dessert, and climbed contentedly into my tent.

- 5 — Jam doughnuts eaten.

Day 5: Gargrave to Malham

Look at that tiddler of a walk! Only 10km. Well, after four days of full-time marching, my feet were starting to fall apart. I had a worryingly deep hole in my right heel, and blisters on my blisters. I’ll spare you more detail. Thus, I had decided to take an afternoon off on Wednesday to keep them clean, dry and rested.

Knowing that a shorter, flatter, sunnier walk awaited me, I felt a zillion times cheerier than the morning before. I quickly reached the River Aire for a tranquil waterside stroll. Baby lambs bounced about as I meandered through their meadows—that sort of thing. I passed Airton and the big, renovated farmhouses of Hanlith, and approached the famed destination of Malham at noon. I found Town Head Farm to camp with splendid views of Malham Cove, and remarked to myself on the number of hand-written, laminated signs around the place.

‘No smoking. Switch lights off. Pay before pitching. Do not leave taps running. No fires. No camping beyond this sign. No noise between 11pm and 6am….’

I need not have feared all these regulations, as I received a friendly welcome. The camping shop had recently closed so there was nowhere to buy gas, the lady explained, and kindly brought me out a cup of tea—my first in three days! I rinsed my socks in the sink and hung them out on barbed-wire to dry. Further bylaws were posted through the afternoon; I kept checking to make sure I remained a law-abiding, lone camper.

‘What network are you on? If you stand in the middle of the main road a bit up from here you can get O2… if you’re tall enough.’

England were playing football later on, so I wandered down to a pub to watch it. Finding it hard to stay awake I left soon after half-time, ready to scale the limestone cliffs of the Cove in the morning.

- 73 — Campsite directives.

Day 6: Malham to Horton-in-Ribblesdale

A lovely morning. I was up soon after dawn, and had my sights on the white crescent of Malham Cove to the north. Just one thing puzzled me: where were the baguettes I’d kept for breakfast? I thought back to the night: I’d woken with a jolt… a push on the tent and a rustled bag… silence…. Fox! The thieving critter must’ve got a paw under the tent and nabbed my petit déj. Ah well, I had some fizzy Lucozade to get me going.

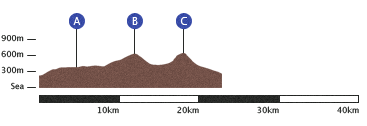

I scrambled up and arced along the crown of limestone pavement to joyfully admire the view back. Nobody else up and walking yet, and not a nimbus or cirrus in sight. The path led across tough grass to Malham Tarn (A), a pretty lake with a grand house on the far side, which the guide informed me had been built by Lord Ribblesdale in the late 18th century as a shooting lodge. I bet the foxes stayed away from his breakfast.

Around the shore past the house, I rose again into open moorland, and hiked up an old miner’s track to lonesome Fountain’s Fell (B). Maintaining my high spirits, I sang Jonathan Richman over and over—sheep scarpering as I called ‘whaddyasay about that, you guys?’ at them like a lunatic. Pen-y-ghent stood imposingly on the other side of the valley. After descending and crossing the road to its southern base, the unswerving incline dared me to take it on.

The shelf which casts Pen-y-ghent’s distinctive profile provided a brief breather in the vertiginous climb, though I was unusually full of energy. Once over the stile at the summit (C) the steep track actually led away from Horton, but promised to bring me there the long way round. I found a farm to camp at but no farmer, despite the alert of barking dogs. I eventually spied him at the back of a large shed full of sheep. I never understand what’s going in these buildings, so I stood tentatively in the light of the doorway.

‘Hello! Here to camp are you? Come down that alley in the middle. That’s it, all the way down. I’ve got a ewe lambing here, and she isn’t going to stop for you I’m afraid.’

The Pen-y-ghent café further up the road looked cozy, so I stopped in for a sandwich and a tin of ginger beer. And there I saw it. Up on the shelf, among a few assorted bits of kit: a gas canister, and unmistakably the model I wanted! After six days, I’d found my fuel. I signed their Pennine Way guestbook (only the second name of 2009) and headed excitedly back to my tent. I pulled out the stove, army tin and couscous I’d been carrying and boiled myself up some dinner. Cooking on gas. Friendly farmer Sutcliffe walked over to enquire how the day’s walking had gone, and where I was off to on the Friday.

I’d been out of phone reception for a couple of days, so I walked back up to the red phonebox to update the folks on progress. I stopped in the Crown Inn for a pint of Black Sheep and quietly observed a village council meeting around the biggest table. I didn’t stay long before calling it a night.

- 625 — ’Radio on’s.

Day 7: Horton-in-Ribblesdale to Hardraw Force

Up and packing to leave soon after six o’clock on Friday, I was somewhat disheartened to find thick mist outside the zipper. What happened to the clear skies of Thursday? I shook as much water as I could from the outer tent and heaved up my bag to go. The friendly farmer waved ‘bye’ from a distance across the field, where I surmised he was off to do something farmy in his wellingtons. I shuffled quietly through the village, past the Inn I’d visited the night before.

A stone-walled path carried me gently out of Ribblesdale, and to my delight I suddenly broke through the ceiling of fog, which I now saw blanketed only the sleeping valley. Above this, I strode in fresh, warm daylight; the disc of the sun rising quickly from behind Pen-y-ghent’s peak. I could hardly contain the bliss of being such a pretty moment, so quiet and early in the day. I suddenly felt strong and young. That is to say, impossibly fortunate. Such reflections are rarer than they really should be. It was certainly a feeling I wanted to savour; one that made it worth all effort expended.

Apart from the distant summits, including Ingleborough—the other giant of the area—the views changed little as I progressed through the morning. One or two shadowy holes suggested locations of the caves indicated on the map. Past Cave Hill (there’s a clue), I arrived at the head of a deep cut in the limestone, Ling Gill (A). Ancient ash trees (and other old species I don’t know the names of) lined the sides of the gorge, steep enough to offer protection from nibbling animals.

‘Anno 1765 thys bridge was repaired at the charge of the whole of West Rydeing.’

The track met the Cam High Road, a well-trodden Roman route over Cam Fell (B). I gained height gradually, overlooking a vast conifer plantation stretching out to the east, before turning left onto a packhorse trail along the edge of a rounded valley. This was one of those sections I underestimated from the map; it took much longer than I expected to reach the highest point, Ten End. From here, however, the view opened out to Wensleydale and more alluring Dales villages.

I eventually dropped down and across a few flat fields into Gayle. The Way enters this hamlet via an ugly pebble-dashed housing estate—something of a shock after a day of walking in open country. It quickly leads on to the larger market town of Hawes, where I dropped my bag briefly for a rest. I was beginning to boil in the afternoon sun. I circled the wonky streets forming the centre of the town, looking for somewhere to find supplies in between the many touristy craft shops. I had to pick up some local cheese in Wensleydale, of course. Once stocked up, I set off toward the day’s destination: the Green Dragon Inn in Hardraw. This pub has Britain’s highest waterfall, Hardraw Force, in its back garden, which I thought would make it a pleasant place to rest for the night.

I was tired and hungry by the time I got there and set my tent up, and rather churlishly admonished the barman when he told me there was no hot water to wash in. I do still think a fiver is a bit much to charge for a patch of grass if you’re not even going to provide a hot water tap. A bath under the falls perhaps? This was where Kevin Costner took a dip for that scene in Robin Hood, so perhaps not out of the question! Other patrons may not have approved. Anyway, I thought the landlord was ‘monetising’ that waterfall a bit much. Apparently it’s two pounds just to have a look at it. It can’t exactly take much maintenance.

The Force is certainly impressive though: a 30m single drop. After checking it out and enjoying my cheese with some bread, I settled down for a late nap. In the evening I went back into the pub to find a cozy seat next to the fire. I spent a while chatting to a sweet couple from St. Helens who were out on their motorbike for the weekend. He wore a Pantera t-shirt and merrily described adventures he’d had on his bike; she seemed genuinely excited about camping ‘for the first time’. I was starting to get used to it. As it was £3.60 for a pint of bitter (in Yorkshire!) I didn’t ask for a second, returning instead to my tent to sip on whisky and listen to the rumbling falls.

- 6.67 — Waterfall price per metre.

Day 8: Hardraw Force to Tan Hill

I knew it was due to rain on Saturday morning and had hoped to be packed up before it started. So I cursed when I woke to patters on the tent not long after five o’clock. I had a plan in the event of a wet start, however. I’d spotted a house-build next to the inn, which had been topped off but not fitted with windows or doors yet. I got all my stuff together inside the tent (quite difficult when everything has to be done lying down) and ran my bag over to drop it in the house. Then I ran back, circled the tent to pull out all the pegs and carried it over so I could take it down and sort my waterproofs out under the protection of a roof.

The morning’s task was Great Shunner Fell (A) and, boy, was I shunned by this mountain. The rain continued to pour, the cloud pressed in on me as soon as I got onto the Fell and the wind only got fiercer as I gained altitude. The outside world disappeared entirely and I had no idea how far I’d gone or had to go. My nifty backpack-covering waterproof poncho only served, in these conditions, as a sail to push me in whichever direction the gales swirled, and to flap up into my face; so I gave up on it, preferring to get soaked. It took no little determination to keep going for hour after hour like this; I repeated ‘HUP! two, three, four…’ continuously to maintain a pace, and shouted crazily at myself to keep going.

The summit cairn offered little protection from the elements and no views, of course, so I continued, northeastward, for more of the same on the descent. As I neared Thwaite (B) and a return to civilisation, I finally passed somebody: a southbound Pennine Way walker. He’d taken eleven days to get to this point, which worried me a little as I only had eight days to cover the same ground. It’s curious to meet someone coming the other way—you each hold the whole trail in your head: part in memory, part in imagination; but you each have the opposite parts. Your near future is their recent past, and vice versa. You try to extract information through questions, ‘what are the best and worst bits to come?’, ‘what’s the Cheviot like?’ and by examining faces for signs of joy, tiredness or fear when they answer.

Perhaps the strain of Great Shunner showed in mine, because before we carried on, he said ‘you know, if you take a left on the first road you get to down there, it’ll take you straight to Keld and chop a couple of miles off.’ As a measure of my weariness, I began to consider the idea. Reaching the road, I paused for a moment and compared the directness of the tarmac with the hike over Kisdon Hill. I carried on—no shortcuts! I soon wondered if I’d regret that decision however, as I got lost on the side of Kisdon. Finding myself at a dry stone wall with no stile, I realised I was a few contour lines away from where I needed to be, and so had to track back for a miserable twenty minutes. On the right path again, I journeyed down through woodland and over some ankle-testing scree, before stopping for lunch next to a river crossing at a small waterfall, where the Pennine Way bisects Wainwright’s Coast-to-Coast walk (C).

Here I had to say a fond farewell to the Dales as I entered County Durham. After an ascent back onto open moorland, I spotted my destination: the implausibly isolated Tan Hill Inn. Tan Hill is the highest pub in England at 528m above sea level, right on top of a remote moor. I had expected it to be somewhat quiet (with the significant effort required to get here from anywhere) but when I arrived, in the afternoon, it was full. I waited at the bar as the man I presumed to be the landlord served drinks. He was a cheery, middle-aged chap with spiky hair (dyed bright red), a black wasitcoat and missing front teeth. A bowler hat later appeared. From the way he bantered with the customers, I think he’d typically be described as ‘a character’. I approved of his swagger in time to the country music on the jukebox. I asked if I could camp. ‘Of course you can,’ he exclaimed, and even kindly offered me a couch to sleep on indoors in the bar lounge. Lovely! ‘The only thing is, this is a wedding party, and it’s likely to keep going late into the night.’ The girls next to me confirmed enthusiastically. So that would be why there were so many smartly-dressed folk then.

I had to consider my options. As much as a comfortable couch in a warm room appealed, I knew I’d be exhausted and would want to be away early in the morning. I didn’t really want to get involved with a wedding. I thanked him and went to set up my tent outside. For the second time in a day, I wondered if I’d made the right call. Being on top of a broad summit, the wind made pitching a tent (even a low one like mine) difficult. At first I looked for the best bit of ground, but the wind just bent the poles flat there. With very little grace I staggered with the tent across to the biggest boulder I could see to use it as a break. Unfortunately, the ground here was at an incline, and was bumpy with stones. What choice did I have? I pitched as near to the boulder as I could stamp the pegs in, and weighed all the sides down with rocks to stop gusts from getting underneath.

I scurried back into the pub to sit down and get warm, and worried about my tent outside. ‘You’ll be fine’ said the barman, nodding to the wind speed meter above the optics. ‘32 miles an hour. We get 50 to 60 here sometimes.’ I was less than reassured, and spent the evening wondering if my tent would get to Kirk Yetholm a few days before me. I’d taken up residence next to the fire to read and, as nobody seemed to be paying any attention, I poked and stoked it a couple of times to keep it burning. Only when I stood up to check on my stuff did I realise my work had constituted an acceptance of responsibility.

‘Where do you think you’re going? You’re in charge of that fire now, son—you’d better be keeping an eye on it.’

So then I had a tent and a fire to worry about.

- 14 — Tent fail windspeed in metres per second.

Day 9: Tan Hill to Middleton-in-Teesdale

Slumped at the bottom of my tent due to the slope, and by then overfamiliar with each of the stones that pressed through the groundsheet, I wondered if it was worth getting up yet. My phone must’ve picked up some signal, as I found a text from my friend Jim: ‘will be at a66 at 8, half eight.’ Where was the A66? Why had he written out the second ‘eight’? Never mind, he was on his way! Jim had kindly offered to join me for couple of days’ walking, and I was really looking forward to having someone other than myself to talk to. Jim’s always fun to have around.

The A66, Ordnance Survey informed me, was about 11km from where my tent was perched upon Tan Hill, so I had to get moving. I struggled to hook out the pegs as my fingers were quickly numbed by the wind. I wanted to move quickly down Sleightholme Moor—to warm myself up and not to leave Jim waiting in a trunk road lay by—but it wasn’t so easy. The guide warned that it ‘can be a dangerous place’, and offered an alternative road route, but I was keen to stick to the official trail and visibility was good enough. The danger, I discovered, lay in tracts of waterlogged peat, into which it’s quite possible to sink deep with a misplaced step. There was little clear path to follow and where I did find it, it was trodden into murky puddles. I set a compass bearing and held it as best as I could.

I made reasonable time, and found myself on the path down to God’s bridge, where a brook disappears under a huge slab of limestone before reappearing again unhindered. And nearby, by the road (A), Jim had just arrived. I showed him where we were headed on the map and we set off vaguely north across Bowes Moor.

The trail met and shadowed a dry stone wall for a long while and, not having to study the compass so much, I prattled on—I hadn’t held an extended conversation with anyone for a week!—and Jim updated me on his York City’s chances of survival in the conference. Reaching the brow at Race Yate Rigg, we then stomped down Cotherstone Moor (the guide puts it perhaps a bit harshly: ‘a sweep of featureless waste’. I thought it was alright) to the gap between Blackton Reservoir (B) and the colossal dam wall of Balderhead Reservoir.

From there we rose uphill through some high, scruffy meadows to a ridge from where we could see out next port of call, Lunedale, and another pair of reservoirs. Passing over the bridge between these, we trekked up through a couple of farms and their scattered barns, to the higher ground around Harter Fell (C). The eerie circle copse of Kirkcarrion, a Bronze Age burial site, stole our attention at the top of the hill to the East.

We finally traipsed onto the road into Middleton at about three o’clock. Having already decided that we should drop our bags soon and scout for a Sunday lunch, we stopped at the first campsite we met on the edge of town. It featured rows of those dreary green static caravans, but offered a space for tents. Looking for a reception, I ventured into the campsite bar/clubroom, which obviously hadn’t been decorated this side of 1990. I waited for a youngster in a Sunderland shirt to swap his coins for Monster Munch before paying to to pitch Jim’s tent: a two or three-manner which seemed palatial compared to the coffin-sized thing I’d been getting used to.

We left quickly to see if we could find somewhere still serving lunch. A couple of pubs had finished up, but the 1618 café held out for us. Though not offering a veggie alternative for the lunch, they were very accommodating and fixed me up a mushroom bake to go with the spuds and vegetables. While we waited, we read the wonderfully local stories in the pages of the Mercury—‘voice of Teesdale since 1854’— whose office sat opposite the café.

Once fed, we wandered over to the Bridge Inn to play a few games of pool. A young mechanic and his girlfriend sat silently next to the window. Sunday in a small town. After pool and a game of darts, we set off back to the tent to read up on Monday’s leg, which would be a serious 30km trek. I took the opportunity to enjoy my first shower in three days. Bliss.

- 3 — Bathtubs in Fields.

Day 10: Middleton-in-Teesdale to Dufton

Despite one or two protests from Jim, and an initial refusal to vacate his sleeping bag, we folded up the tent and set off reasonably early. The day promised a scenic riverside mosey and visits to the famous waterfalls of Low and High Force; the latter holding the title of biggest waterfall in England by volume6. This section comprised the dogleg of the Pennine Way trail; for a whole day we’d be walking west, rather than making any direct progress north toward my destination in Scotland.

I was a bit concerned to discover, when stumbling out of the tent, that the knee-ouch I’d suffered towards the end of Sunday’s leg had not gone away as I’d hoped. By this point, I’d had several spells of pain in a hip, ankle or foot, but had walked each of them off. This one seemed more persistent, very sore and, moreover, coincided with an injury I’d received playing football a few months prior. I could hardly put any weight on my right leg without a stab in the outer side of the joint. ‘How can I keep walking on this?’ I felt sick at the thought of not finishing after I’d made it all this way. I gulped a couple of Ibuprofen tablets down (the first I’d used so far) and set off with a bit of a hobble. At least the morning’s terrain, accompanying the meanders of the River Tees, would be relatively undemanding.

The first part actually cut off a couple of the windier turns of the river, heading through pastures and over stiles. Soon we were on the river bank again under a canopy of trees. Massive white bags of pavement littered the path for a distance, ready to be laid soon. In their current position though, they were obstacles around which we had to weave and squeeze. Thankfully, the painkillers were now working, dulling the sharp discomfort to a more tolerable ache.

The three cascades of Low Force announced the start of a dramatic stretch of rapids and whirlpools. As we continued excitedly up toward High Force (A), the path teasingly took us away from the river, returning just at the south bank viewing point for the falls. It is a spectacular plunge over the dark slab of Whin Sill7. We paused for a drink.

As the roar quietened behind us, the Way left soft pastures for heath and higher ground. The Tees veered off to the right as we went over a small hillock. It came back to meet us again and we crossed over a footbridge near to Forest-in-Teesdale—the only habitation visible in the opening panorama. As is not unusal for us, Jim and I got on to discussing the brilliance of Half Man Half Biscuit and soon discovered that theirs made for great walking songs. Thus, much of our day hoofing it through remote wilderness was soundtracked by shouts of ‘They’ve got a German Shepherd dog called Prince, the one called Sheba died…’ and so on.

Falcon Clints required some arduous scrambling over cliffs as we met the Whin Sill up close. It took almost an hour to cover what looked like a short distance on the map. ‘Twisted ankles and broken hips are regular mishaps on this section,’ warned the Guide. We eventually turned the corner to Cauldron Snout (B), another crashing cascade just below the dam of the Cow Green reservoir.

The trail then passes for a distance along the edge of Warcop, a vast MoD firing range. There are signs near the path warning ‘Keep out or we might shoot you’ (or words to that effect). We childishly creeped off the path a little to see if we could spot anything, but nothing seemed to be going down. Perhaps they were having a day off, or else they were all disguised as rocks.

We left the Tees at the reservoir to follow its tributary Maize Beck, and were soon walking out over a featureless expanse between distant Fells. This sort of stretch can be draining. We had to cross the Beck at a footbridge, but Jim decided to hop across rocks in the shallow water. After that, he began to lag behind me. This was the second longest leg I would complete in the fortnight, and he’d only been walking for one day so I certainly sympathised. I remembered how much I’d been suffering on the second and third days up to Blackstone Edge and Ponden, and realised I’d built up some stamina in the past week of full-time walking.

Now into the afternoon, I thought we’d just have a prolonged slog into Dufton to go but Jim pointed out that ahead was an impressive-sounding feature I’d missed in the Guide: High Cup. The astonishing view that greeted us at High Cup Nick (C) was one of the highlights of the whole Pennine Way. I now realised why we’d spent a day walking west, away from the eventual destination: this was breathtaking! High Cup is an immense, broad and perfectly symmetrical glacial valley, with the cliff of the Whin Sill forming a vertical rim. Due to the way the Way brought us to the top ‘nick’ of the valley, the view was an utter surprise as the landscape suddenly disappeared from below us. We stood at the edge trying to take in the scale and throwing stones off to vanish toward the distant valley floor.

After this rest, we followed around the north edge of the valley, still admiring the views, for a lengthy descent into Dufton. Jim had decided that he wasn’t ready for a third day’s walking on Tuesday—quite reasonably, especially as it would include the Pennines’ highest Fells—and so was intent on finding some way of returning to York that evening. With his encyclopedic knowledge of the British railway network, he realised that nearby Appleby-in-Westmorland was a stop on the Settle–Carlisle railway, which would connect.

We’d hoped to enjoy a pint in the Stag Inn before he left, but on arrival it was mournfully closed. Possibly as it was a Monday; Dufton is not a real place. At the same time, checking the train times and spotting an ‘Appleby 3½’ sign, we realised he didn’t have long to get there before the last train. And just to improve matters, it started raining. Off he ran.

I found the (empty) campsite to set up my tent, and quickly got everything inside. Miserably, there was nothing for me to do in Dufton but lie in my tent listening to the rain. Oh well, at least I could boil up some hot food and make a cup of tea… except, stupidly, I’d allowed my matches to get damp. I could not get a single one in the pack to light. Bah! And then my tent began to leak right above me. Wonderful. I put my army tin under the drip, opened a packet of biscuits and sipped on whisky.

I received a message from Jim at around 8 o’clock.

‘Not one single bloody lift! Did a double time jog to Appleby in rain then up bloody big hill to get to station with 2min before last train. Now speeding back through Dales…’

I was glad, and not a little amazed, that Jim had made his train home. I had a bit further to go yet.

- 38 — Soggy Matches.

Day 11: Dufton to Alston

Rain was not what I wanted for the hike over the fells to Alston but I’d been fortunate with weather this far so I couldn’t protest much. I pointlessly tried to shake some of the water off my tent and got going.

The route skirted west of the steep, conical Dufton Pike and soon left the calm pastures of the Eden Valley for more forbidding Pennine heights. I knew I was to take on the biggest of the lot today, and that this was not the weather for it. Well, I’d slogged in rain before and could slog again.

The first ascent was Knock Old Man (A), at 794m. This is a significant climb from the valley floor. Just as on Shunner Fell, I lost all visibility as soon as I’d gained a bit of altitude and the wind picked up. Unable to use landmarks, I was perpetually checking my map and compass. The path was not obvious and, suddenly, it disappeared entirely. I had imagined some vague marks into a pattern, which vanished like a mirage. I searched around, and decided to track back on my bearing. I found a fork I’d missed in the fog, indicated by what in ordinary conditions would’ve been a prominent rock, with an arrow pointing right where I’d gone left.

Taking greater care now, I made my way to the Knock summit. The force of the wind encouraged me off again quickly. Reaching the bottom of the dip before the next climb, I stumbled across tarmac. This was very peculiar—why was there a metalled road so high up? The Guide informed me that it is, in fact, the highest road in Britain and that it heads up to the Radar Station on top of Great Dun Fell (B), at 848m. This conspicuously huge white ‘golf ball’, along with assorted masts and small buildings, watches air traffic over the North Atlantic, and would purportedly lead me to the summit: ‘No one will ever get lost trying to find Great Dun Fell in anything short of white out conditions.’ I suppose this was ‘white out’ then, because I couldn’t see a thing. The path was navigable, however, and I met the facility’s perimeter fence over which, right in front of me, was a huge white sphere I couldn’t make out the edges of. I shivered in the wind, and in the alienness and isolation of the place.

I carried on quickly to Little Dun Fell next door, only a jot littler at 842m. It is more of a ridge connecting its neighbour and Cross Fell. The side wind hit me even harder here, and I had to crouch into it. I spotted a small stone shelter and decided I’d run to it for a breather before the final push. As I slumped back on my rucksack, I turned to find a sheep’s skull on the rock inches from my face—as if it wasn’t unnerving enough up here. Just one more.

If I’d studied the topography of Cross Fell (C), I probably wouldn’t have got myself into trouble. The top was in fact a plateau, about 1km wide and nearly 2km long at a maximum height of 893m. As I was now a little tired, I didn’t scale it properly from the map. It had a brim of scree, which had to be scrambled up. At this point, several routes split but all seemed to lead to a tall cairn at the top. The wind up here—on the very top of the Pennines—was incredible. I could only open the map page in the miniscule shelter the cairn offered, and set off on the West Northwest bearing to find the summit marker.

There was no path at all. I kept checking for the obelisk behind me but it soon disappeared. It felt wrong—no markers and no foot erosion at all. I tracked back and found the tall cairn again. I reset my bearing and zigzagged a little to search for a trail. No sign. I stopped again to think, and realised I was getting very cold. I only wore a t-shirt and breathable jacket while walking so I would often get chilly if I stopped, but in this gale, soaked through, I was going to freeze if I didn’t keep moving.

Then, out of the fog, I saw a new cairn to the left. I headed straight to it. It was stupid of me not to check the bearing I was taking. It turned out to be just a pile of scree, and led nowhere. Now I was lost. It took most of my energy just to restrain from panic. ‘Keep calm and think.’ I decided I’d keep west, find the edge of the plateau and follow it north, where it had to meet the path to descend on the north face. Though not the easiest or most direct of routes, it would surely get me there. I strode with my head down into the howling wind and beating rain, checking each step to avoid turning an ankle on a rock or in a hole. There were still pockets of snow up there. I manically repeated, ‘Where’s the path? Where’s the path? There’s got to be a path.’ I had been up there a long time and was shivering, lost, slightly terrified and very alone.

Though poorly cited when I write, the Wikipedia article on Cross Fell gives some idea of it not being the most comfortable of places:

‘The fell is prone to dense hill fog and fierce winds. A shrieking noise induced by the Helm Wind is a characteristic of the locality. It can be an inhospitable place for much of the year. In ancient times it was known as “Fiends Fell” and believed to be the haunt of evil spirits.’

Finally, I found something. It was eroded only slightly, but had to be heading the right way. ‘Path. Path. Path…’ I murmured senselessly. Then it was gone again. But by now I was heading down the north side of the hill (forget the summit marker, I wanted off), and I knew I had to meet a miner’s track crossing perpendicular. I hit it. Just to the right I saw an isolated dwelling through the fog; it had to be Greg’s Hut, marked on the map as an emergency shelter for anybody stranded up there. Relief! Joy! I knew where I was, and I was safe.

I thought about sitting in the hut for a bit, but after sheltering behind it for long enough to get my breath back, I decided to march on. It would all be downhill from there. After half an hour or so I met three southbound Pennine Way walkers, the first people I’d seen all day. I was very glad of it. They were in good spirits, and one was even wearing sunglasses in the rain, which may have had something to do with him being Australian; I wasn’t sure. I told them to be careful, and described my fright up on the fells, but they didn’t seem to be taking me seriously. Perhaps they found their way over just fine.

I can’t remember much of the rest of the afternoon; Cross Fell kept going through my head. My trousers were frozen to my legs as the rain persisted. The long track descended all the way into Garrigill (D) before a quiet riverside walk to Alston.

Before I’d set off back in Edale I’d decided I would allow myself to make use of a hostel every few days to break from camping, though I hadn’t needed one in the first ten legs. The YHA at Alston was on the approach to the town, and I decided I could do with a proper rest. It was a great little place: the chap running it was friendly and helpful, I got a room to myself for £15, there were teabags and someone had even left a chocolate cake with a ‘Please Eat Me’ sign on it. I took a shower and hung my socks to dry in the laundry room. My friend Dave surprised me with a call from Calcutta to see how I was getting on and offer some encouragement.

It was wonderful to have a bed. I wouldn’t have to wear my hat and gloves and curl up in my sleeping bag. I wouldn’t have to turn over every time my sides went numb. I wouldn’t wake up at dawn shivering. I had a pillow.

- 736 — ’Where’s The Path?’s.

Day 12: Alston to Greenhead

Over breakfast at the hostel, I chatted to a couple on my table who were on a driving and cycling holiday.

‘I did the Pennine Way—well, nearly did it—twenty years ago now. I got to Bellingham and fractured my shin jumping off a stile.’

Ouch! I still had a couple of days walking before Bellingham, so I certainly wouldn’t be jumping off anything before then. I devoured as much breakfast as I could, including three Weetabix, eggs, veggie sausages, mushrooms, beans, hash brown and a whole rack of toast with marmalade.

I’d read that this leg would likely be the dullest of the Pennine Way but, to be quite honest, I’d had quite enough excitement with Cross Fell the day before so I wasn’t too bothered.

The first section followed a road and railway north through the valley of the South Tyne. On the left slope of the valley, I hopped over stiles through farmland. The only item of note was Whitley Castle (A), the remains of a Roman auxiliary fort. I didn’t spy it initially, only realising up close that the narrow undulations near the path were actually the remarkable rhomboid ramparts of this second-century stopover on the Maiden Way, which connected a fort on the York–Carlisle road with Carvoran on Hadrian’s Wall.

Continuing north, the route took me across the road and under the railway into Slaggyford. Leaving the river, I passed under a pleasing arched railway viaduct, through more farms into Knarsdale and joined that old Roman Maiden Way over Lambley Common.

After Lambley, the route left the road I’d followed all morning to head out over desolate moors. Hartleyburn and Blenkinsopp Commons were big, open hills and the hike—mile after mile of slow climbing—was tiring. The vague ramble west eventually brought me to the fence I would follow all the way to to the top of Blenkinsopp (B).

Eventually, I weaved my way through abandoned mine workings to the noisy A69 road linking Carlisle and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Unfortunately, the quickest way into Greenhead was to walk behind the highway barrier, over the service station fast-food wrappers and cola cans that so many idiots had discarded from their windows; trying not to breathe in too much lorry exhaust.

Greenhead seemed quite uninteresting. Its main preoccupation seemed to be with the big road. It was hardly village-like. I fancied a pint but the hotel didn’t look appealing. A campsite was suggested on the map, so I headed straight for it.

A little old lady, in her seventies or eighties, called from behind me as I walked up the road; she’d seen me walk too far with that big rucksack on. ‘Are you looking for camping?’ she asked, in a lovely half-geordie, half-scottish accent. She led me back to the green lawn behind her pretty house. ‘We’ve not had anyone yet this year, but you’re welcome to stay.’ We had a short chat about where I’d been and where I was off to next. Bellingham was a long way to go in one day, she thought. As she hadn’t mentioned payment yet, I asked how much it was. She frowned as though she didn’t really want to charge. ‘Oh, three pounds it is love. My son looks after the camping usually, but he’s away just now. You’ll need twenty pence pieces for the shower, do you have any?’ I didn’t, so she put four in my hand and tottered back into the porch.

I showered, performed my daily replacement of the plasters holding my feet together and cooked up some couscous as the shadows of tall conifers stretched long across the grass.

- 2.5 — Litres of Lucozade.

Day 13: Greenhead to Bellingham

I packed up early from the garden in Greenhead, but the sweet old lady was up by the time I was leaving and waved me off from the porch, opening the front door to wish me ‘good luck!’. I waved back and walked down the hill back into the village. As I consulted my map for the correct path leading north to Thirlwall Castle and Hadrian’s Wall, a man in a somewhat incongruous ten-gallon hat came over to point me right. In that same half-geordie, half-Scottish brogue which seemed to me the nicest thing about this place, he told me he’d always wanted to do the Pennine Way, and wished me well. Walking alone for days, these little encouragements really cheered me up and having received two before I’d even got going from Greenhead, I had a spring in my step.

Thirlwall Castle was built from stone taken from the Wall and the nearby fort of Carovan. It sounds like historical vandalism but in the violent borderlands of the Middle Ages, keeping alive against the best efforts of marauding mobs was clearly more important than preserving heritage. The Way meets and follows the Hadrian’s Wall Path here, another National Trail tracing the length of this World Heritage Site. Eager to see the Wall, I got a march on past the few morning dog-walkers.

I’ve visited the Wall before on a family outing, but it was just as exciting to see again up close. Not only did it represent a significant marker on my journey (‘I set off from Derbyshire, and I’m all the way up here!’), but it’s such an impressive work of engineering. Augmenting the already towering northern face of the Whin Sill—that same lump of Dolerite that we met at the Low and High Force waterfalls, where the Tees falls off its southern edge—the barricade stretches 117 km (80 Roman miles) across the width of Britain. And once you’ve applied a little imagination to picture the original five metres of stone that stood up from the foot of the ramparts, the forts and turrets, the ten thousand troops in service, even the emperor himself striding across the land inspecting the merciless wastes to the north, it can’t fail to enthrall.

This time, alas, I knew I’d need to be disciplined in limiting the time I had to enjoy views and explore forts, and plough through the 10 km to Steel Rigg relatively quickly. I was tackling two of the recommended day sections in one go, so a good early pace was essential. But stomping up and down the steep undulations of the Sill was unexpectedly sapping, and I was contending with a painful right knee. Since Middleton, I’d had to chomp Ibuprofen as soon as I woke to reduce the soreness enough to get it moving, but the big steps here were agony and I was beginning to worry again if it would stop me getting to Scotland.

The morning went on, and I passed energetic bunches of youngsters brought out on half-term excurstions by their parents, gleefully disobeying the ‘Please don’t walk on the wall’ signs. I considered it myself—who doesn’t like balancing on a wall? Through the Aesica fort, and along Crawfield Crags, I passed some English Heritage workers painstakingly fixing a bit. I suppose you still can’t be too careful with the Scots. Up on Windshields Crags (A), I reached the highest point of the Sill. Here I paused to look north and get my first glimpse of my final opponent, the superboss: The Cheviot. That dark, whalebacked hill stood out menacingly on the horizon. ‘See you in a couple of days.’

I descended to Once Brewed, gazing north the whole time as I reached the final section of wall I’d cover. ‘A fascinating and threatening place, it must’ve seemed like the end of the world to the Romans,’ says the Guide, and I wouldn’t disagree.

Before Vercovium, the Pennine Way departs from the Hadrian’s Wall Path and heads north between Greenlee and Broomlee Loughs. By this point, it felt like I’d done a day’s walking, but I wasn’t even half way. At least these marshy fields were less work for my knee. Here I entered my first proper covered section, Wark Forest. The dark woods enclosing the path certainly made a change from the exposed moorlands I’d gotten used to. I entered a clearing, with a stone the Guide told me marked the spot legend has it a local chieftain was slain by one of King Arthur’s chums, or something like that. ‘The desolation of the place may cause you to hasten on your way.’ No doubt.

Finally leaving the forest for grassy moorland, the route became a bit difficult to follow, but I managed to find the concealed waterfall I was looking for at Warks Burn (B). Through a couple of farms, I caught up to, and walked a short way with, a couple who were taking the Way in sections. I marched on to the grandly- and amusingly-named Shitlington Hall, and then a while later stopped at the end of a large field with no exit in the barbed wire. I stood confused as the sheep smirked at my stupidity. I grumpily retraced my steps and found the sign I’d missed, hidden behind a parked old Mercedes at the farm. Shitlington indeed. Trudging up a hill to the relay tower that was my next target, I embarrassedly greeted and passed the couple again.

The long walk on boring tarmac into Bellingham reintroduced me to every ache and pain in my legs and feet, but the final stretch through the quaint town, along the bank of the North Tyne in the evening light, raised my mood.

I found the farm I was looking for, which offered camping, and took a shower. The facilities here were great! I could use a cozy room in a converted barn, with a basic kitchen and a lovely potbelly stove in the corner to warm by. This would beat lying in a cold, wet tent. Bellingham had a Co-op, from which I bought a big bag of stuffed pasta, a huge apple pie with a tub of double cream, and a couple of cans of bitter.

On returning, I found other guests at the farm: a group of friends, in their 40s or 50s perhaps, who’d started at Kirk Yetholm a few days before and were walking the Way southbound. They set out to find a pub, but left sitting by the fire was a chap silently sipping tea. I joined him once I’d eaten, being careful not to disturb his peace, and we slowly got to talking. A German professor of East Asian languages, he was on a cycling holiday around the north of England, which he talked of fondly. He’d been at Durham for many years, he explained, and loved the landscapes here. He talked about the joy of exploring slowly, taking time to stop and enjoy views, as opposed to trying to get countryside ‘done’. Often feeling I would like more time to stop in places along my journey, I appreciated this sentiment. Now and then I prompted him with questions about his travels in Japan and Korea, and he seemed happy enough to talk while I was happy to listen. He had a quiet temper of the kind I would like to age into.

When the others returned, we talked more jovially about walking and other adventures, and I must admit to feeling a little proud when they roundly commended me on making it so far. The atomsphere by that potbelly stove was really pleasant. When I went to bed, booming snores resounded around me, but after all that walking I was soon out cold myself.

- 4 — Roman forts.

Day 14: Bellingham to Byreness

Following the 30-odd kilometres covered the day before, this penultimate leg through the Kielder forest promised to be a lighter piece before the finale over the Cheviot hills and into Scotland on Saturday.

Happily, I was also walking to meet my mum and dad, who were driving up to meet me in the afternoon. They’d kindly offered to collect me at the end of my walk so I wouldn’t need to negotiate the buses and trains back home. Better still, dad had decided to join me for the final leg, after enjoying our walk from Crowden to Blackstone Edge two weeks before, so this would be my last day of walking solo.

Leaving Bellingham at 8 o’clock, north towards Blakelaw, I passed ruins of mine workings, and the remains of a coal railway track. Via the stiles of Hareshaw House, I met and crossed the B road to Otterburn, and slowly climbed the moorland to Deer Play (A), ‘a wide wilderness with limitless views’, and up to the summit at Whitley Pike. The next ascent, Padon Hill (B), had a tumulus built on top by the owners of Otterburn Hill in the 1920s. The growing mass of Kielder approached, and down at Brownrigg Head I reached and followed its edge for a distance, apprehensively looking under the perimeter of trees into the dark within. Cold steam rose from the canopy. The path led me in at Rookengate, at which the woods swallowed me for the day. It’s a little hard to describe the feeling of being deep in those acres and acres of Norway Spruce. It gets repetitive much sooner than being up on a barren hill or on an open plain, where at least there are usually distant vistas to give some distraction. Here there were only the closest trees, the gloom beyond, and a persistent sense of unease. I imagine a better understanding of nature would help, as one would be able to appreciate the birds and small variety in trees, but to me it was the same one hour to the next. And so my mind would drift into considering the size of the forest, and how easy it might be to disappear into, and if there weren’t people living in there unknown to the rest of the island. Escaped convicts, even! And then a twig would snap and I’d hurry on my way.

Forests are great though. It’s fun to imagine what England must’ve been like before so much of it was chopped to make way for agriculture and settlements. Cities and towns, all oak and birch. Kielder is, of course, a modern addition—grown in response to timber shortages following World War I, it’s a huge mass of Norway Spruce. Yes, a mixed and native woodland would be more appealing, but I reckon this is better than no forest at all.

I escaped the dark and reached my destination at about three o’clock. I called mum in the car, as dad drove, to boast that I’d beaten them there. As they were still an hour away, I decided to explore the village. It took all of five minutes—Byreness is not a place. Built by the Forestry Commission to house forest workers (who were soon replaced by machinery) it consisted of a couple of ugly cul-de-sacs, a closed-down pub and a decrepit petrol station. A pretty Methodist church offered its only reprieve. The camp site was back down the main road, so I was glad to be getting a lift. The petrol station had a little shop and a couple of picnic tables, so I decided that would be the best place to wait. I dropped my bag and glugged on the Lucozade I had left from the Bellingham Co-op. I had intended to investigate the shop and pick up a snack, but as the cashier (or owner, or whatever) came to the window to give me a pointedly scornful look (presumably as I had stopped to rest my legs before buying something from them) I decided they were getting no pennies from me.

It was great to see mum and dad, share hugs and sit in a warm, familiar car. We drove down to the campsite. It turned out this place also had rooms available, which they kindly came back with keys to. So we’d have comfortable beds before the last effort. Even better, they drove me to a restaurant in Otterburn, where I hobbled through the lounge on my battered feet to enjoy a big tasty meal. I was still apprehensive, remembering the tales I’d heard of the Cheviots along the way, remembering how hard it was to do 30 or 35 kilometers, remembering how dangerous Cross Fell had been and that The Cheviot was even more infamous. Would my knee make it through a day of 40 kilometers over even more big hills? Would there be enough daylight, even setting off at dawn? I was certainly glad dad was going to be coming with me. This was going to be tough!

- 13 — Plasters holding feet together.

Day 15: Byreness to Kirk Yetholm

I jumped out of bed after just a few thuds of the heart with the alarm clock’s wail. From all the tales I’d heard of the Cheviots — from journals, books and other walkers I’d met on the way — I’d been anxiously thinking about this day for weeks. And here it was, our own Chevy chase. Could we really do these two huge legs in one day?

At the first hint of dawn, dad and I quietly gathered our packs, sticks and maps, and set off down the road to the little church in Byreness to rejoin the Way. My apprehensiveness was lessened somewhat by the clear brightening skies — the weather vowed to be kind at least. We turned right off the road and with early freshness attacked the first abrupt climb out of the valley floor, giving us 400 metres of height quickly and getting our legs moving.

With the forest now falling below us to the left, we ventured north but quickly met some of the soggiest ground I’d met in the whole walk, with no boards or stones to offer assistance. It was frustrating to spend so much time moving sideways in search of viable routes and often having to turn back when we came to dead ends. Dad was finding it a bit harder than me to traverse the bogs, and after a while we realised that the plastic skirt around the spike on his stick had broken off — so while I was finding small patches of grass to pole vault from, he was sinking straight in to the mud.

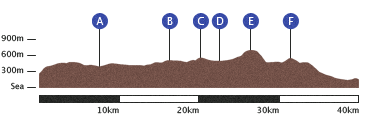

More Ministry of Defence signs warned us not to touch any military debris we might come across as we aimed for some ancient military debris: the Roman marching camp of Chew Green (A). The camp was a stopover on Dere Street, the colossal highway ordered by Governor Agricola to connect Eboracum (modern-day York) with the shores of the Firth of Forth.

We followed this Roman road north now deeper into the wilderness of the border hills. We were making excellent time moving at top hiking speed, and I worried we might tire ourselves out while full of adrenaline.

We passed a mountain refuge hut before climbing up to Lamb Hill and then Beefstand Hill (B) at 562 metres. At this point, dad and I both started to feel pain — me once again in my knee and dad in a hip. After weighing up our options, we chomped down the painkillers we’d brought in the hope that they’d keep us going at this pace. It meant we wouldn’t have any to call on later, however.

The imposing peak of Windy Gyle (C) lies right on the border between England and Scotland, marked by a fence that we tracked right to the top, where stands Russell’s Cairn. Centuries ago, the wardens of the violent borderlands met upon these empty windy peaks to negotiate truces. At once such meeting on this very spot, discussion turned sour and Lord Russell was violently murdered in cold blood.

The Guide remarks

Desolate… with violent and sinister associations, Windy Gyle is one of the atmospheric highlights of The Pennine Way.

For the first time, we crossed over the border — I had walked to Scotland. For now we didn’t advance far into the country as the Way follows the border fence closely, crossing back and forth. We dropped along a ridge to meet another ancient road, Clennell Street (D). We were making excellent progress — my target for this half-way point was one o’clock and it was only noon. The Guide recommends stopping here if there are fewer than six hours of daylight remaining, as it is possible to walk several kilometres north to a track where a car pick up can be arranged. From here on in, there would be no short escape before Yetholm.

We spotted several wild goats out on the heather-covered slopes on our way to Kings Seat, and up to meet the point where the route branches to the summit of the Cheviot (E). Having gazed at that shadowy humped hill getting closer over the past few days, and with the weather sunny, we saw no reason not to take the five kilometre detour.

Soon we wondered if we’d made the right choice, as the wind got fierce and the flat, long rise to the top was entirely covered with the deep, dark mire. This was a really tough stomp. Reaching the top, we sheltered behind the cairn to regroup and chomp down sandwiches and biscuits. The views from the summit aren’t the best because it’s such a domed hill, but catching sight of the North Sea out towards Bamburgh and Seahouses—where we’d spent a lovely beach holiday when I was small—was exciting.

We didn’t hang around long up there before stomping our way back down through the bog. After wasting a lot of time on the way up trying our best to avoid the deeper pools, we realised the futility and just marched as straight as we could on the way down, which led to some comically deep drops into mud.

Arriving back at the trunk path, we dived down the sheer slope west to a second refuge hut, taking a curious look in through the window. We scaled a high border ridge with stunning vistas to the left and right, struggling our way to the top of The Shill (F). Though lower than The Cheviot by a couple of hundred metres, this summit offered a splendid full panorama of the hill range under crisp blue skies. We paused to breathe it all in. This, we thought, was the last big climb of the way, and it deserved to be savoured.

On the descent from the Schill, dad and I were both really suffering from our injuries, and completely out of painkillers. My knee was agony, and dad’s hip was the same. We were limping, slowing down and running out of energy. At the bottom, the path forks and two options are available for the final section into Kirk Yetholm: appropriately, the high road or the low road. The latter is suggested if the weather is bad or daylight is running out. As appealing as the low route was with the pain we were in, I hadn’t come all this way to miss out hills at the very end. The high road it was.

After the good work we’d done on the climbs so far, that of White Law was the hardest all day. The vertical trudge seemed to last all afternoon — we just couldn’t get to the top. At this point we were walking quite apart, dad needing to walk a little slower. I had been practicing for two weeks, remember, and dad had matched me all day on the longest and hardest leg, which was impressive!

From White Law we were finally, finally, finally on the descent to Kirk Yetholm, between lower, greener hills, across the ford of another trickling burn and onto a tarmac road: the home straight. Of course, this being the Pennine Way, it was still another mile or so on the hard road and now we were seriously limping, just trying to drag our tired legs to the finish line.

Early evening light poured into the valley, and I felt a strange mix of relief, apprehension, pain, pride and some sadness. The adventure was nearly over. Here it was, Kirk Yetholm, the mystical name I’d murmured to myself so many times over the last fortnight. I thought back to the moment I stepped off a train in Edale, rested my foot on a dry stone wall, adjusted the straps on my backpack and took a first step which led me all the way here.

Staggering down into the village, we spotted my mum, who’d arrived in the car with perfect timing to meet us. The official end of the Pennine Way is the bar of the Border Hotel. Exhausted and happy, we limped into the dark pub to procure celebratory pints. We carried them back to enjoy at a bench in the warm Scottish evening sun, and mum surprised me with a bottle of champagne. Bitter, bubbly, family and the joy of pushing my battered and blistered feet into that cool grass — glorious!

- 9 — Counties visited.

Thoughts

I felt a bit strange for a few days afterwards. I’d completed the toughest physical challenge I’d ever given myself, which felt great, but what to do now? For the past two weeks I’d known exactly what I needed to do all day long: walk. Now I was back to real life, where I constantly had to make decisions about how to spend my time. And that is hard, isn’t it?

Except, I realised, that I didn’t need to make these decisions all the time; I was just doing it because I’m that kind of a worrier. And I realised it’s a huge waste of time. I can get far more and far better things done if I stop prevaricating, procrastinating and questioning myself constantly. I should just see what I ought to do and then resolve to do it. Along with the incredible vistas I’ll remember for a lifetime, that’s probably the most important thing I took from two weeks of silent reflection on the beautiful hills of northern England. Now I’m rested and recovered, I can’t wait to get back up there.

It’s a cliché, but I couldn’t have done this walk without my mum and dad. Their pick-ups and drop-offs made the logistics possible, and I borrowed nearly all the equipment I needed from them. They even bought me the new boots I walked in. So this is a big thank you to them. Thanks to my grandad Ronnie, who supplied me with two weeks’ supply of Capt. Scott’s Expedition Biscuits. I had to survive on those for a day and a half before I got my stove working. Thanks to Jim, who was great company for two fine days to break up the solitary walking.

I doff my walking hat to Tom Stephenson (whose idea the Pennine Way was), National Trails for keeping it well maintained and the ramblers of the 1932 mass trespass of Kinder Scout8, who fought for our right to roam this beautiful island.

Summary Data

| Day | Distance (km) | Ascent (m) | Time Walking (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.5 | 911 | 6½ |

| 2 | 28.8 | 1,005 | 8 |

| 3 | 30.3 | 924 | 9 |

| 4 | 25.1 | 776 | 8 |

| 5 | 10.0 | 241 | 3 |

| 6 | 24.1 | 560 | 7 |

| 7 | 22.9 | 852 | 6 |

| 8 | 24.1 | 1,077 | 7 |

| 9 | 29.2 | 551 | 8 |

| 10 | 36.4 | 561 | 10 |

| 11 | 31.4 | 1,069 | 8½ |

| 12 | 26.6 | 577 | 8 |

| 13 | 34.3 | 920 | 10 |

| 14 | 23.7 | 544 | 6½ |

| 15 | 40.0 | 1,620 | 11 |

| Sum | 414.4 | 12,188 | 116½ |

Footnotes

The distance varies in each account I read (paths are fractal-like and difficult to measure), but 429 km (268 statute miles) is what the National Trails guide reckon. A sum of my day measurements is 414 km. According to my feet, it’s a long way.↩︎

Whenever I refer to ‘the guide’, I mean the National Trails: Pennine Way South and North by Tony Hopkins.↩︎

I later also awarded full marks to those who labeled Dismal Hill and Foul Step.↩︎

The worst I had to deal with on this leg was being chased by some big hungry pigs near East Marton. I actually yelped when I saw the first fat thing coming towards me.↩︎

After a few days walking, I began to instinctively check for taps in each settlement I arrived at, whether I needed water or not. How’s that for bushcraft, Ray Mears?↩︎

Hardraw Force, which I had slept next to on Day 7, features the highest drop.↩︎

I have hardly referenced the geology of the Pennines while describing my walk, having a pathetic knowledge of rocks beyond ‘hard stuff, that’. But I was not unaware of the importance of it during my stomp; indeed, one of the helpful National Trail leaflets mapped out the different ‘depositions’ and ‘intrustions’ making up each area I passed through, and offered a nice quote to convey the importance: ‘To look at the scenery without trying to understand the rock is like listening to poetry in an unknown language. You hear the beauty, but you miss the meaning.’ — Norman Nicholson. The feature called Whin Sill is noteworthy. It is a particularly hard slab of igneous Dolerite that squirted up, in molten form, from below the crust before solidifying between layers of existing rock. As this softer rock has eroded around its edges, the Dolerite is exposed in remarkable cliffs. Here at High Force, it is the precipice over which the Tees falls. Its northern edge, Hadrian decided, would make a good base for a defensive wall.↩︎

The first hill I climbed!↩︎